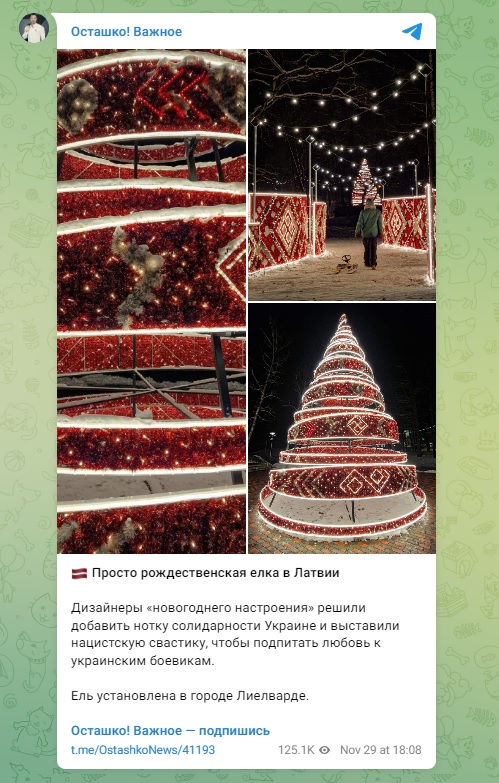

In November 2022, various media outlets and Telegram channels reported that a Christmas tree installed in the Latvian city of Lielvarde was decorated with a pattern in the form of a swastika. We checked the accuracy of these publications.

On November 30, Russia’s Channel One aired a short news story on the Christmas tree, which had been recently installed in the city of Lielvarde. “In Latvia, they’re creating a New Year's mood with a Nazi flavour,” the presenter said. On November 29-30, materials with similar headings were released by other Russian media such as Komsomolskaya Pravda (“Latvia decorates Christmas tree with swastika”), Izvestia (“The Latvian city decorated with “Christmas swastikas” for the New Year”), Ren-TV (“Council decorates city near Riga with "Christmas swastikas"”) and RuBaltic (“Latvian city’s Christmas tree decorated with swastikas”). They were joined by Armenian and Uzbek services of Sputnik (“Bright decorations and a swastika — “holiday” tree put up in Latvia” and “Swastika as a national symbol: Christmas tree decorated in Latvia”, respectively). Ruslan Ostashko, a Russian TV presenter, went even further. On his Telegram channel (341,000 subscribers), he claimed that the Nazi swastika was used in the decorations as “a note of solidarity with Ukraine” that which “should fuel love for Ukrainian militants.”

To begin with, the photos and videos presented in the media and social networks are real. Many Latvian media outlets, such as Delfi, TVNet and TV3, as well as locals on social networks, reported that an unusual Christmas tree had been lit up in Lielvarde on November 27. But did Russian media and Telegram channels interpret these publications correctly?

On November 28, the official website of the Ogre region, which includes Lielvarde, described how the local authorities prepared for the Christmas holidays. This year, instead of real Christmas trees, the council opted for design installations in three settlements. In the pictures from Lielvarde, it is easy to see that the city’s park is decorated not with a tree, but with a spiral tapering upwards made of artificial materials. According to the press release, the designers decided to use the traditional element of the national costume, which comes from this particular region of Latvia — the Lielvarde belt.

According to Zane Nemme, curator of the Lielvarde Museum, the history of these belts dates back to the 12th century. There are several dozen of them in the collection, and the oldest specimens were crafted in the first half of the 19th century. The traditional Lielvarde belt is dyed red and white, sometimes green, blue or purple threads are woven into it. But the main feature of this piece of garment is a rich and varied geometric pattern, including various types of crosses.

Latvijas Kultūras kanons, the website created by the National Library of Latvia, shows patterns of the Lielvarde belt from the beginning of the 20th century — some of them show figures similar to a swastika. The same ornament on the belts was shown to journalists in the Lielvarde Museum in 2018. Similar belts are also shown in the documentary, which was shot in 1980 by Ansis Epners, the director of the Riga film studio.

In Latvian, this symbol is called ugunskrusts, which means "fiery cross". The National Encyclopedia of Latvia says that the first archaeological finds decorated with this cross and discovered on the territory of modern Latvia date back to the 3rd century, and the symbol began to be used in textiles already in the 11th or 12th century. In the 1920s, even before the Nazis came to power in Germany, Latvian folklorists actively studied this symbol and the meaning it had for their ancestors. At the same time, the fiery cross began to be used on the emblems of army formations, state awards and book covers in independent Latvia. For example, an edition of Latvju dainas was published by writer and folklorist Krišjānis Barons in 1922 and decorated with ugunskrusts.

As the National Encyclopedia of Latvia emphasizes, local radical nationalists included the fiery cross in their symbols. In 1932, the Latvian national association Ugunskrusts appeared. This far-right party did not have much success, it was reorganized and changed its name to Pērkonkrusts (“Thunder Cross”, as this symbol is also called) in 1933. A year later the organization was banned, although it continued campaigning (still without any serious political achievements). During World War II, this association collaborated with the Nazis at first, but the Reich authorities quickly banned it as well.

At the same time, the National Encyclopedia of Latvia explicitly states that "at the international level, this symbol is known by the word “swastika”". “The view of the fiery cross as an auspicious sign and Latvian cultural heritage often conflicts with the negative connotation of the symbol associated with Nazism, World War II crimes, the Holocaust and racism. Therefore, its use today is unacceptable for many”, the article says. According to its authors, to avoid negative associations, sometimes a distinction is attempted: the swastika "rotates" clockwise while the fiery cross does the opposite. However, both versions of the symbol were used in traditional Latvian patterns.

In modern Latvia, there is no public and common concern that variations of the fiery cross have been used in the heraldry of some regions for centuries. On the other hand, in 2013 the symbol was already the subject of a scandal during the Christmas holidays. Then, a lawmaker from a local nationalist party baked gingerbread cookies in the form of a “fiery cross”, hung them on a Christmas tree, made a picture of them and posted photos on social networks, which caused a heated discussion in Latvian society.

Displaying the swastika and other Nazi symbols in Latvia is prohibited by law (except for its use for educational, scientific or artistic purposes), but this rule does not apply to the fiery cross in the context of the national ornament. Determining which of the two identical symbols is being used and in what context is often difficult. For example, on the day of the centenary of the Republic of Latvia in 2018, a participant in the festive procession brought a white banner with the symbol in the colours of the Latvian flag. Journalists identified the man as Igors Šiškins, a right-wing radical activist who was imprisoned for trying to blow up the Victory Monument in Riga in 1997. The police did not see any violations in Šiškins' actions; however, after public outrage and the publications in the local media, the police opened an administrative case on the public use of the swastika. A few months later, the court ruled that there was no proof of the activist’s behaviour (the judges probably decided that the flag depicted the fiery cross, not the swastika).

In a way, the Finnish Air Force found itself in a similar situation once. The swastika had been depicted for decades on its emblem. Observers from the outside resented the use of Nazi symbols, although in this case, the sign was a tribute to Eric von Rosen who founded the local military aviation. In 1918, he presented Finland with its first aircraft and painted a blue swastika on the fuselage — "his personal symbol of good luck." Nearly a century later, the Finnish Air Force changed the emblem to a golden golden eagle in a blue circle, and this was done specifically to avoid confusion by outsiders.

Latvia is not ready to abandon the use of the fiery cross just because of its similarity to the swastika. Unlike the case described from Finland, here it is part of a national ornament, known for many centuries. According to those who came up with the Christmas tree in Lielvarde, the installation referred specifically to the Lielvarde belt, and its ornament traditionally includes this symbol. Does the design of that Christmas tree use a combination of lines that can be identified as both a fiery cross and a swastika? Yes. Do the designers thereby refer to Nazi ideology and, moreover, “feed the love for Ukrainian militants”? No.

Cover photo: Ogres novads

Half true

- Latvijas Kultūras kanons. Lielvārdes josta

- Nacionālā enciklopēdija. Ugunskrusts

- Is it true the Finnish Air Force's emblem was decorated with Nazi symbols until recently?

- Is it true the students in Lviv formed into the form of a swastika on Hitler's birthday?

- Is singing Katyusha banned in Latvia now?

Если вы обнаружили орфографическую или грамматическую ошибку, пожалуйста, сообщите нам об этом, выделив текст с ошибкой и нажав Ctrl+Enter.